Optimizing Performance in Unreal

I’m often shocked by how commonly I hear people say that Unreal is not performant. That it puts more emphasis on visual fidelity and not on FPS. I think that this is a very common misconception. Yes it is true that compared to some other game engines, Unreal has put a lot of development effort behind making it EASIER to achieve high quality visuals… but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t possible to get a high FPS in your games, or even that it’s all that hard to do so.

I think that it is largely a product of Epic’s marketing, as well as the marketing of some of the games that have been built with Unreal, that this idea has emerged amongst the communities that use Unreal professionally or personally. People see that Unreal is capable of all these incredible visual feats, and flock to it wanting to replicate those things in their projects.

Rocks - far as the eye can see

Lumen, Nanite, Raytracing, Volumetric Effects, etc. are all very flashy and they get a lot of attention… but not always from game developers. In fact, it is because of all of these things that Unreal is leading the charge in Virtual Production technology. Disney, Universal, Sony, and many more have all adopted Unreal-centric pipelines to author their content for LED walls, and sometimes even beyond that using it as early as pre-production and post-production to conduct more rapid visual development cycles before taking the plunge into final visual effects. In some cases it’s taking on the role of final visual effects and even end-to-end final pixel animation.

Predator: Killer of Killers was fully rendered out of Unreal

But what if I told you that it’s just as important for all of those use-cases to have good FPS? Would you believe me? Well it is 100% the truth and I know from experience. Every creative team that works in Unreal for linear content production needs their in-editor performance to be buttery smooth to be able to live up to the promises that ‘realtime’ makes for productions, whether we’re talking about games, live action virtual production or animated features. The demand for quicker turnarounds and shorter production timelines is greater than ever before, and if it takes an animator, lighter or visual effects artist hours to make a turnaround on a creative note on a shot, that’s killer to a production schedule. Animators working in-editor particularly need to have smooth realtime feedback to dial in performances, but the same goes for every creative department.

Everything that is added to a shot in service of a story needs to be able to play back at a minimum of 24 fps in the case of animation. Compared to the 60-90 fps target that most modern games aim for, that will sound very low, but 24 and 30fps are the common frame rates for animation and film. In the case of virtual production - fps needs to be as high as possible during performance capture or the actor’s performance won’t be accurately recorded, leading to more reshoots and money spent on set. Not the place you want to be wasting time.

All of this is why I wanted to write this article. This is intended to be part guide for technical artists working in both games and linear content production, and part wakeup call for producers, business development manager, directors, and project managers. The success of your real-time projects depends on the management of a single resource: Video Memory.

Why Video Memory?

Video Memory, aka VRAM, is the amount of short-term storage a graphics card has to manage data relating to graphics and video processing. Even that can feel like a bit of an outdated definition, because vram is leveraged as much for audio and all-purpose AI tasks nowadays as it is purely for video processing. Trying to use ComfyUI or some other AI tool to generate pictures or videos? That’s using your VRAM. Trying to transcribe audio clips to text? Also likely using your graphics card. And generating models, texture, vfx, or rendering your cinematics / game in realtime? One hundred thousand percent using your GPU VRAM.

You should really watch the 1982 Tron if you haven’t yet. Ironically, dedicated VRAM was barely a thing then and

you’d be lucky to get 16KB on a PC that would’ve cost $3,000 at the time, or $10,000 in today’s market.

Now there are very low levels of data management that are better saved for a computer science degree lecture to cover this, but I want to talk a bit more about how the average technical artist or non-technical artist or non-graphics programmer can take steps to avoid bottlenecks on the VRAM that can cause the FPS in the projects to take a nose dive, or cause their render times for the cinematics to skyrocket.

The Usual Suspects

This is going to be the short list and summary section covering the things that usually spring to the front of my mind when artists reaches out to me saying ‘I’m getting really bad in-editor performance’, or when we have done a recent new build for our game and are seeing massive FPS drops during playtesting.

Lighting

This is one area where people are very quick to turn every knob and lever they can reach up to 11, and not think twice about the consequences. Lumen and other forms of global illumination, raytracing, volumetric clouds, godrays, emissives, all of these things come at substantial VRAM costs. Whether it’s for games or linear content, you have to ask yourself not just ‘do we need this?’ but also ‘do we need this if it means we can’t have ANYTHING else fancy?’ because that often ends up being the case. If a light shaft can be a card (texture), it should be. If a shadow doesn’t need to be soft, it shouldn’t be. If you are lighting a large area, a directional light is probably a better choice than point light. If you’re not flying through the clouds, why are they volumetric? There are so many ways to achieve a good look without making everything physically or scientifically accurate, and games have been using those techniques from the very beginning. Cheating lighting isn’t a new thing, it’s just forgotten in the modern era.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit - 1988; Animators painted every frame by hand to get the lighting to work in this shot and have it feel natural. Sometimes doing it the hard way is worth it.

Textures

One of the more common mistakes I see is people bringing in all of their textures at 4k, or sometimes even higher. I think the misconception is that if you want your product to hold up on a 4k monitor, that all of your textures also need to be 4k. That couldn’t be further from the truth though. The key concept to be aware of here is Texel Density - in short, how many pixels on the screen is a given asset going to occupy at any point in time. The only things that need to be 4k are things that are going to fill literally the entire screen, and even then, they only need to be 4k in that moment. If we’re talking about a character’s face / eyes, and we have a close up during a cinematic, great, lets get some 4k eyes in there. But the second we punch back out or go back to looking at the character’s back, if we’re still storing those 4k eye textures in vram then we’re missing out on vram resources that we could be using for high quality environment lighting, visual effects, or impactful gameplay moments. Most of the time, face and eyes probably don’t need to be more than 2k, and often even less. If your game is first person or third person over the shoulder… why would you even render eyes?

If you can’t see pixels, it’s good enough!

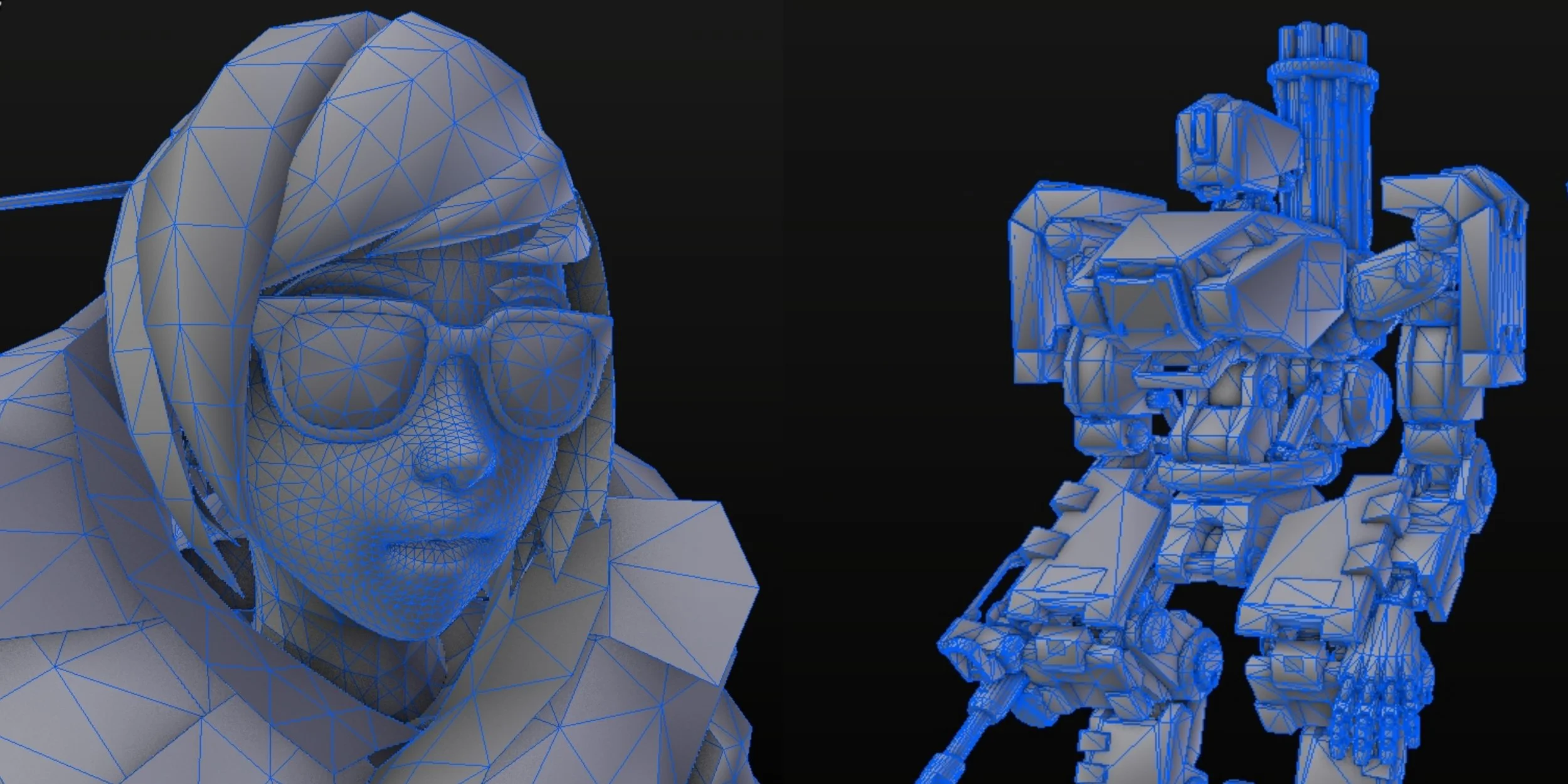

Polycount

‘But Brett, we can just use nanite for everything!’ No, shut up. This is one of the most important takeaways from this article. If you skip everything else I’ve written here you should internalize this. If you think you can just use nanite for everything you don’t deserve to use it for anything, and certainly shouldn’t be trusted to use it for anything. Here’s the reality - nanite is an incredibly powerful optimization technique and a remarkable innovation of the modern Unreal Engine versions, but it comes with SO MANY costs. The problem is if Epic led with all of the bad, nobody would care to use it. When you elect to use nanite in your project, you are actually signing up for a boat load of constraints and highly specific workflows for your lighting and shading as well. If you are rendering cinematics or making a game for someone else and need to hit specific art direction, oftentimes nanite will in fact get in your way and prevent you from being able to achieve those looks. When that happens, you need to be able to fall back to an efficient model topology anyway. And even if you are using nanite, fewer polygons still means better performance. Taking it one step further, if you are working on anything that needs to be animated, if you don’t have good clean topology, you will never get good clean animation. Full stop. Learn how to retopologize properly, it will save your life and your production.

Overwatch wireframes. The pros use efficient topology, so should you.

Effects

Where do you even begin with effects? Almost any form of effects needs to be handled with extreme caution. Think of it just like you are handling real life pyrotechnics. You wouldn’t just pound gunpowder into a ball with a hammer and then light the fuse while holding it. The most important things to consider in Unreal when it comes to effects is that less is more, and dispose of them properly. It’s kind of the same as I mentioned with lighting above. Does this need to be volumetric? Or can it be a single texture. For how many frames is it visible? Have I completely destroyed the actor after it has served its purpose? If we’re getting specific, there are a lot of things that Niagara can do in Unreal that, more often than not, you just shouldn’t use at all. Light emitters? Just don’t. Niagara Fluids? Very cool, but unless your name is Asher Zhu, or you are only using it for a cinematic, you probably shouldn’t be messing around with it. If it is critical to your gameplay loop, you just have to keep in mind that you will need to make greater sacrifices in every other area to make sure that your VRAM can accommodate it, and even then you will still need to find ways to make sure that is as performant as possible.

League of Legends vfx breakdown - They are often simpler than you’d imagine, and that’s why you can spam them without your computer exploding.

Blueprints

Here’s the big one for the developers out there. Stop using event ticks! Or more specifically, just be extremely mindful of whether or not you need it for what you are trying to do. 99% of the time whatever it is you think you need an event tick for, you don’t, and you should actually be using something else as the trigger for your logic. Chances are that an interface call, or dispatch are what you should be using instead. The thing with event tick is that it runs all the time… meaning it is always occupying some of your budget, and your resources for the rest of your game are permanently reduced. That’s literally the worst case scenario. Resource management (gpu vram, standard ram, cpu, or even disk space / hard drive space) means that we want things to occupy those resources only when they absolutely need to, and then free up that space so we can do more things. Imagine you are juggling. You could be the BEST juggler and still have a limit of 11 balls (I checked, that’s the actual world record), after that if you want to add something else into the routine, you have to drop something else to make room. If something you are working on 100% without a doubt needs to use an event tick, then you should be considering how you can make sure that thing can exist for as short a period of time as possible.

It’s like not having enough pylons in Starcraft, except you can never build more, and neither can your users.

User Interface

Another big one for developers, more specifically the UI/UX folks. Canvas panels in Unreal will also tank your performance. In general, a highly performant game can get roasted alive by a poorly optimized interface. They suffer from the same restrictions when it comes to textures, just like mentioned above, but it's even more dire because in most cases they are present the entire time, meaning just like the concern with even ticks, you are making the choice to limit your permanent resource budget that is available for… the rest of the game. Some of the best things you can do here, besides avoiding canvas panels and using other things like grid panels, size boxes, scale boxes, overlays, etc. instead, is to - just like vfx and blueprints - make sure that if something isn’t being used, it is removed. This means entire UI elements, but also UI features, particularly hit-testing. If part of the UI does not need to interact with the mouse, it shouldn’t.

Example of a bad UI. Except these are actually done for humor and are genuinely amazing. This one is by a dev that goes by ‘theMutti’ - https://www.reddit.com/r/badUIbattles/comments/ug4cbj/a_cursor_controlled_by_a_fan/

Honorable Mentions

One thing worth mentioning specifically is Render Targets. It’s almost too easy to fall for this trap. Maybe you’re trying to fake a reflection, maybe you’re trying to make a minimap, or do that cool virtual-runtime texture blending thing or interactive grass world-position-offset animation trick you saw online. A lot of roads lead to using Render Targets… but the bad thing about them is that, unlike some features of Unreal, they do not default to the most performant settings, and often in fact default to the worst possible settings. ‘Capture Every Frame’ and ‘Capture on Movement’ under the ‘Scene Capture’ section both default to on, and the Capture Source defaults to Scene Color (HDR) If anyone at Epic reads this… please for the love of god change these settings. For anyone who hasn’t realized it yet… What this means is that you are drawing your entire scene… again. On every frame.

This is a recipe for literally HALVING your FPS with a single actor. I’ve done it, I’ve seen almost every other Technical Artist / Technical Director / Developer I’ve worked with do it. It’s like a rite of passage. Let this be your warning, and maybe save you hours of headache or possibly make you the optimization hero your production needs. If you have low FPS, and your project has render targets, check these settings. Disabling capture every frame can give you immediate gains if your render target is always active. The trick to using them and keeping performance good is controlling when they do and don’t capture, reducing the rate at which they capture, or reducing the quality of the image they capture. If you can have your render target only capture at 12 or 24 fps, that’s orders of magnitude more efficient than capturing at 90+ fps. If they don’t need to capture the scene and perfectly replicate every intricate light and shadow, that will also help lighten the load considerably.

What could go wrong?

The last one here is similar but more about just working in the editor in general, and won’t help with regards to the performance of a packaged / built game… but having multiple viewports open while you work in editor, and having them all in fully lit mode… is basically the same issue as the render targets. You’re asking your GPU to draw your entire world multiple times. Some users will think that this is rare or nobody really does this but trust me, if you swear up and down that your project has good performance but your team’s animators, lighter or other creative team members are constantly flagging poor editor performance, just ask them how many viewports they have open. The answer will probably surprise you.

You really don’t need this.

Conclusions

In summary, it’s not that Unreal has poor performance, it’s that modern graphics capabilities have created an expectation of this high bar for visuals in our minds as gamers or content creators. It’s important to consider however, that if we are creating a product that we intent to be interactive, or even if we are trying to create a cinematic that is going to be rendering out multiple frames to then be played back later, that there is going to be a point at which ‘how long does it take to render a frame’ becomes a critical consideration. The best time to have that consideration, is before you have created a situation where making sacrifices becomes more painful than it could’ve been otherwise. Being faced with the challenge of optimizing visuals after a look has already received creative buy-off is not where you want to be.

Do tests early and often. Have conversations with your creative team members and directors, and decide as a collective what is more important - taking advantage of every single new high-end visual system Unreal, or any other software has to offer? Or delivering a product on time, on budget, and at a good FPS that won’t induce motion sickness in the people who play it.

Good performance is, in fact, a choice.

Find something useful here? Have questions about your own projects? Or have examples where optimization saved your life and your product that you want to share? Join The Atlas Problem’s Discord server and tell us about it.